Last spring, third graders in Wilcox County, Alabama—which has the highest rate of economic disadvantage in the state—beat the odds. According to the Public Affairs Research Council for Alabama (PARCA), 96% cleared the state’s reading benchmark, and by the end of summer literacy camp, every single student had passed.

Meanwhile, 900 miles away in the Rust Belt district of Steubenville, Ohio, third graders are rising to the same occasion. Despite serving large concentrations of low-income students, Steubenville consistently gets 95-99% of kids to read proficiently.

Neither Wilcox nor Steubenville fits the stereotype of a “top performing” school system. But in both places, children are learning to read—and doing so at rates that rival (or exceed) the wealthiest communities in America.

That’s not supposed to happen. Poverty has long been one of the most stubborn predictors of educational outcomes. And yet, a handful of school districts are showing us what it looks like to disrupt that narrative.

The gains in these districts didn’t happen in a vacuum, though. They reflect the potent combination of proven policy changes and interventions paired with the not-so-common political stamina that it takes to stay the course.

As Alabama’s Finance Director, Bill Poole, told me: “You can have the best policy ideas in the world, but if you don’t have the implementation to go with it, the outcomes may not follow.” Poole knows a thing or two about what it takes to ensure continuity. Before taking the helm as the state’s “CFO,” he spent eight years as the state’s chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, which oversees the state’s Education Trust Fund (ETF).

- In Alabama, the latest surge in literacy outcomes can be traced to the passage of the 2019 Literacy Act, which sparked a statewide effort to improve reading instruction with a corps of reading specialists and school-based coaches, thousands of teachers retrained in the “science of reading,” and targeted support for high-poverty districts like Wilcox.

In the years since, the state has been steadfast in implementation under the leadership of Gov. Kay Ivey (now in her eighth year as governor) and Eric Mackey, who stands among the longest-serving state superintendents.

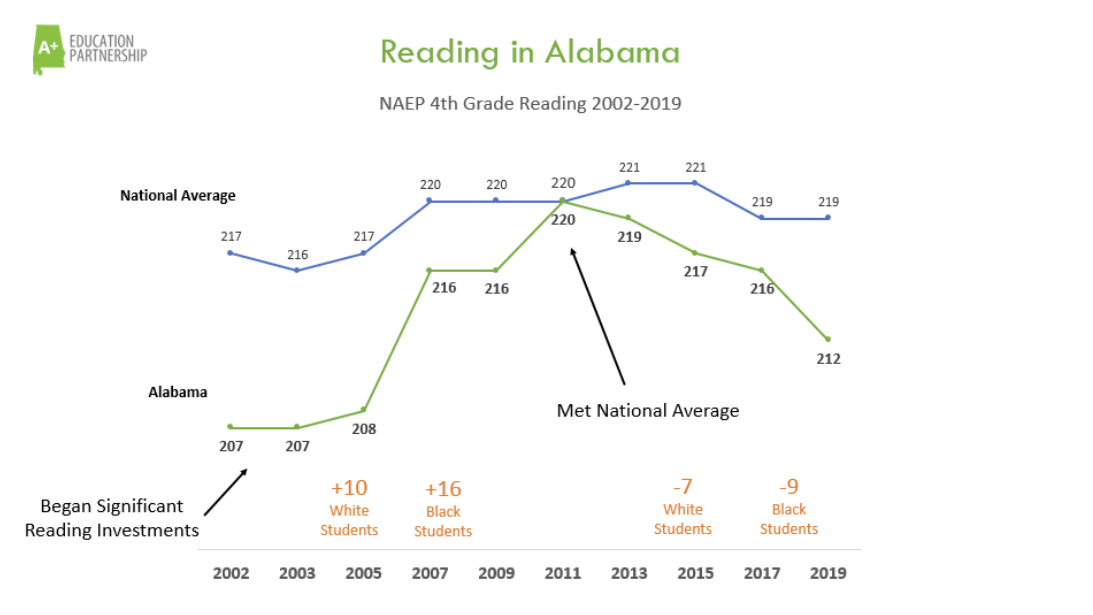

But Alabama’s history also offers a cautionary tale. This chart from the A+ Education Partnership depicts a decades-long march toward the national average under then Gov. Riley’s leadership. Sadly, those gains proved ephemeral: as leadership wavered, the state experienced steep declines before the latest Literacy Act-driven surge.

- In Ohio, Steubenville’s success is likewise linked to stability and continuity. The district has maintained the same superintendent for more than a decade, low teacher turnover, and a 25-year commitment to the same reading program. Every teacher—including PE instructors—leads a reading block, and subsidized preschool gives students a head start in literacy, language, and writing.

History tells us that poverty predicts performance. Wilcox and Steubenville suggest otherwise. The challenge for policymakers, educators, and funders is clear: are we willing to do what it takes to turn these outliers into the norm?