On June 30, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the Biden Administration’s proposal to cancel $10,000 of federal student loan debt for every borrower who, in either 2020 or 2021 earned less than $125,000 (or $250,000 for those married, filing jointly, or heads of households). Under the Administration’s proposal, recipients of federal Pell Grants would have had up to $20,000 of student loan debt canceled.

The opinion of the Court, delivered by Chief Justice Roberts stated that “…the Secretary’s new ‘modifications’… were not ‘moderate’ or ‘minor’” and “instead, they created a novel and fundamentally different loan forgiveness program” (pg. 19).

Over the last few months, the legality of how the Biden Administration sought to implement their proposal has been called into question.

And, I know a thing – or two – about the authorizing statute in question. In 2001, I was part of a policy team with the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Education and the Workforce that wrote the original legislation, the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act,” or the HEROES Act, which was introduced by Representative Howard P. (“Buck”) McKeon following the attacks of September 11, 2001 and the national emergency, declared by President George W. Bush on September 14, 2001.

The original HEROES legislation was tied only to the national emergency declared on September 14 and any subsequent national emergencies declared by the President as a result of terrorist attacks. I vividly recall working on this language – and candidly, praying that we would never again, as a nation, need to declare another national emergency for the reason of a terrorist attack on the United States.

The legislation was passed unanimously by the House of Representatives, and alleviated the hardship of student loan debt for borrowers affected by the attack.

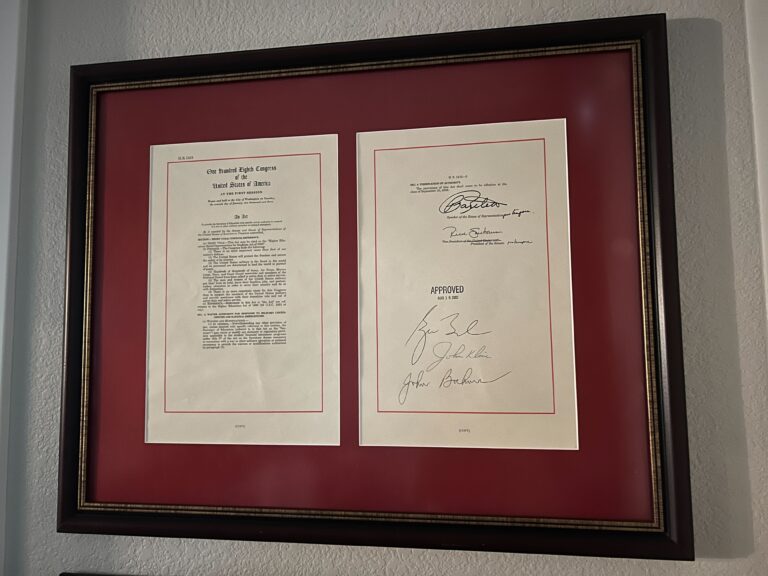

In 2003, Representative John Kline introduced H.R. 1412, which is what we know as today’s version of the HEROES Act. This legislation was introduced shortly after the United States invaded Iraq, and provided service members, who were both deployed and volunteering for service and others affected by war and natural disasters, access to administrative flexibility granted by the U.S. Department of Education (ED). A quick review of the Congressional Record (and the Amicus Brief filed by Congressional Republicans) does note that over the last twenty years, the statute has been slightly amended, but never written to authorize a broad loan forgiveness policy.

The 2003 legislation was approved and signed by President George W. Bush on August 18, 2003 and authorized the Secretary of Education to do one thing, as written:

The Secretary of Education may waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision applicable to the student financial assistance programs under Title IV of the [Higher Education] Act as the Secretary deems necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency to provide the waivers or modifications authorized by paragraph (2).

As a lifelong advocate for college affordability and access, streamlined federal financial aid and increased accountability in higher education, I am a proponent of policy ideas that can make a big and immediate impact on college cost, including debt forgiveness.

Although today’s decision from the Court is disappointing for some, it’s not surprising to those of us who have been engaged in the student debt debate for decades. And while the Administration sought to provide student debt forgiveness for a cohort of borrowers through the application of the HEROES Act, the reality remains that the federal law governing higher education – the Higher Education Act – is long overdue to be reformed through a comprehensive reauthorization. The pressure for needed reform of the student loan program should now be redirected to and exerted on Congress.

Interested in more expert policy analysis on the issue of student loan debt? Reach out to the Whiteboard Advisors team.