As is often the case, change in Washington happens very slowly. Until it doesn’t. And then it comes at you fast.

Dave and I first met in the early 2000s. I was in the very early innings of advising edtech startups and investors on the implications of a sweeping new law known as the “No Child Left Behind Act.” Dave was advising states and school districts at a law firm founded by a couple of lawyers who had advised on the spin-out of a new education department from the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare decades earlier.

It’s strange to think that less time passed between the formation of the Department and NCLB, than has passed from NCLB to today.

For the last few months, we’ve been reporting on the prospect of an executive order (EO) intended to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education (ED). It finally happened on March 20.

In the wake of the EO, there has been no shortage of applause and outcry. But most of all, there has been confusion. With good reason.

The president’s executive order could have very real implications for not just federal workers, but students, families, and the millions of educators, professors, and administrators who manage schools and institutions nationwide. It is no doubt fueling anxiety among student borrowers who have been whipsawed by new policies, legal challenges, and uncertainty in recent years. Notwithstanding well-documented concerns, it could also create new efficiencies and provide the sort of flexibility that states and districts have asked for.

On March 21, President Trump announced his intention to shift aspects of IDEA administration to the Department of Health and Human Services (which is already responsible for programs like Head Start and school-based Medicaid) and student loan debt management to the Small Business Administration. The day prior, Senate HELP Chair Bill Cassidy (R-LA) stated that he would introduce the necessary legislation to close ED. To pass, that bill would require supportive Democrats to clear the 60-vote threshold in the Senate.

To be sure, redesigning the governance and administration of federal programs is a big deal. And while it’s far from unprecedented, it’s not typical either. Given the pace of change in Washington over the last 25 years, change on this scale no doubt feels foreign to many in the education sector.

So where will it all land? We’re not sure. Our newsletters and blog aren’t intended as forums to editorialize or conjecture. And we can’t possibly address—or assess—the impacts on every facet of ED at this stage. That said, here are four points worth noting:

Title I

Title I is part of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), which President Lyndon Johnson signed into law in 1965. The purpose of the law is to supplement state and local funding in schools that serve high concentrations of low-income students. Congress last reauthorized the law in 2015 and the law still requires that the funds may only supplement, and not supplant, state and local efforts to improve academic programs for students who struggle to meet state academic standards. The latest federal annual appropriation (FY25) provides $18.3 billion to eligible schools across the country. It’s not going anywhere.

IDEA

President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act into law in 1975, which became the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA) in 1990. The law is bedrock for students with disabilities because it provides parents with a private right of action ensuring the development and delivery of the individualized education plan (IEP) for their child. Congress last reauthorized IDEA in 2004, and Congress appropriated $14 billion in FY25 for the program.

This, too, is not going away. On March 20, before the EO was signed, Secretary McMahon reiterated in a podcast interview that the protections and funding under IDEA will not be touched.

Federal Student Aid

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Higher Education Act of 1965 into law, making the federal government the primary provider of student financial aid. The Federal Student Aid (FSA) office was created to manage the financial assistance programs authorized under Title IV of the same law—including those distributed via the FAFSA and the student loan portfolio—and has always operated under ED. President Trump has made it very clear that the EO will not impact the disbursement of Pell Grants or students currently receiving and accessing loans. What’s less clear is what will happen to student loan repayment programs, which the Trump administration and Congress are likely to target as a source of federal savings in the upcoming Budget Reconciliation process.

It is worth noting that major changes in the administration of the Department’s $1.7 trillion student loan program aren’t new. In 2010, the Obama administration fundamentally restructured the loan program by shifting all loans to “Direct Lending” and eliminating the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program and guaranteed loans.

In recent history, repayment policy has also been fickle, with substantial repayment changes taking place from Bush, to Obama, to Trump, to Biden, and now back to Trump. Most recently, the Biden administration proposed sweeping forgiveness and new income-driven repayment pathways, which were both challenged and ultimately stopped in the courts.

Other agencies have always been in the mix

While ED has historically been responsible for implementing a broad portfolio of education programs created through federal statutes, many of the most significant programs are not implemented by ED. For instance, the National School Lunch Program, created in 1946 under President Harry Truman, provides about $17.2 billion in services and is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provides about $7.5 billion for school-based Medicaid services. The Office of Head Start, also at HHS, provides about $10.4 billion to over 1,700 public and private organizations to operate Head Start programs.

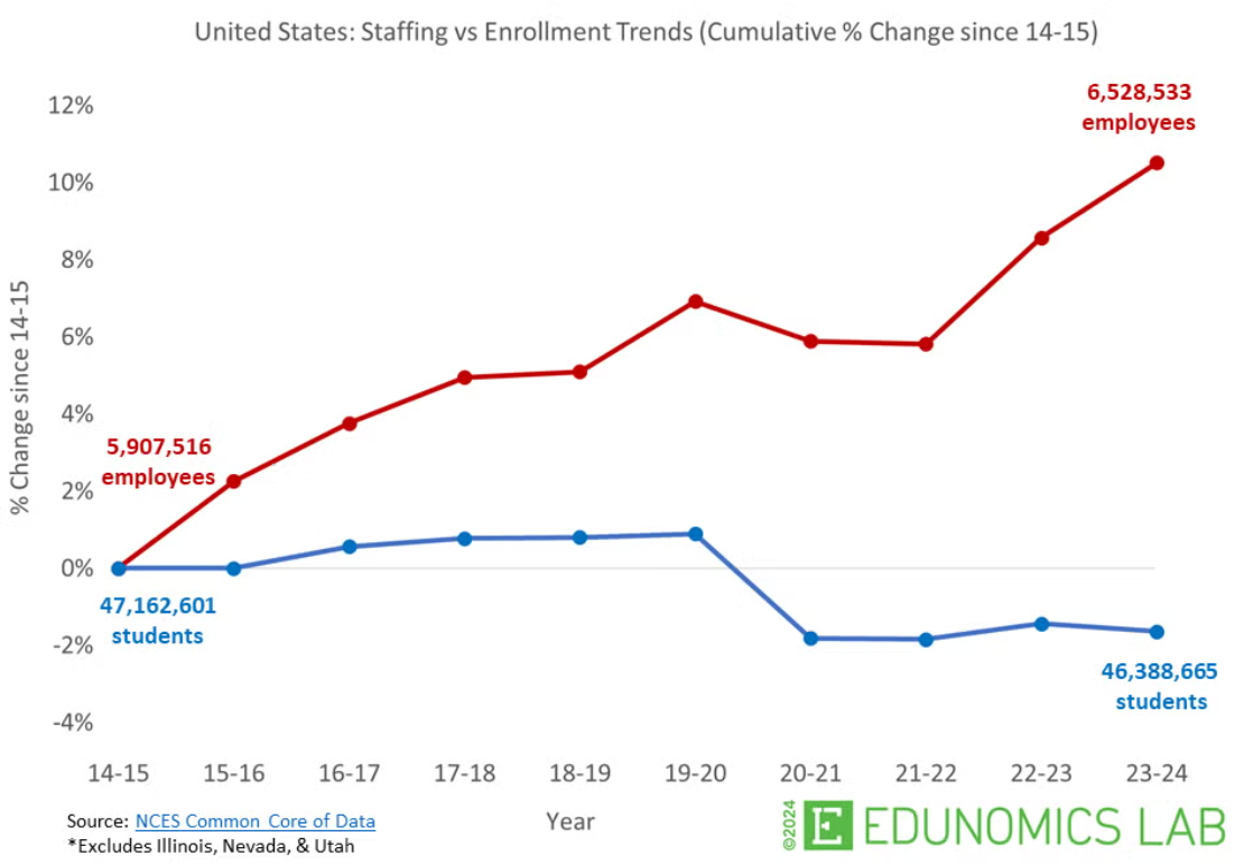

Of course, shifts in education policy never occur in a vacuum, and we’ve been in the midst of tremendous transition—even before the EO was issued. At the K-12 level, schools are closing the books on $185 billion in stimulus funding as concerns about the economy rattle state and local budgets. The chart below, from W/A Senior Advisor Marguerite Roza, offers a striking depiction of K-12 wrestling with a hiring hangover and declining enrollment. What it doesn’t show is chronic absenteeism rates are up from 15% prepandemic to now 26% nationally.

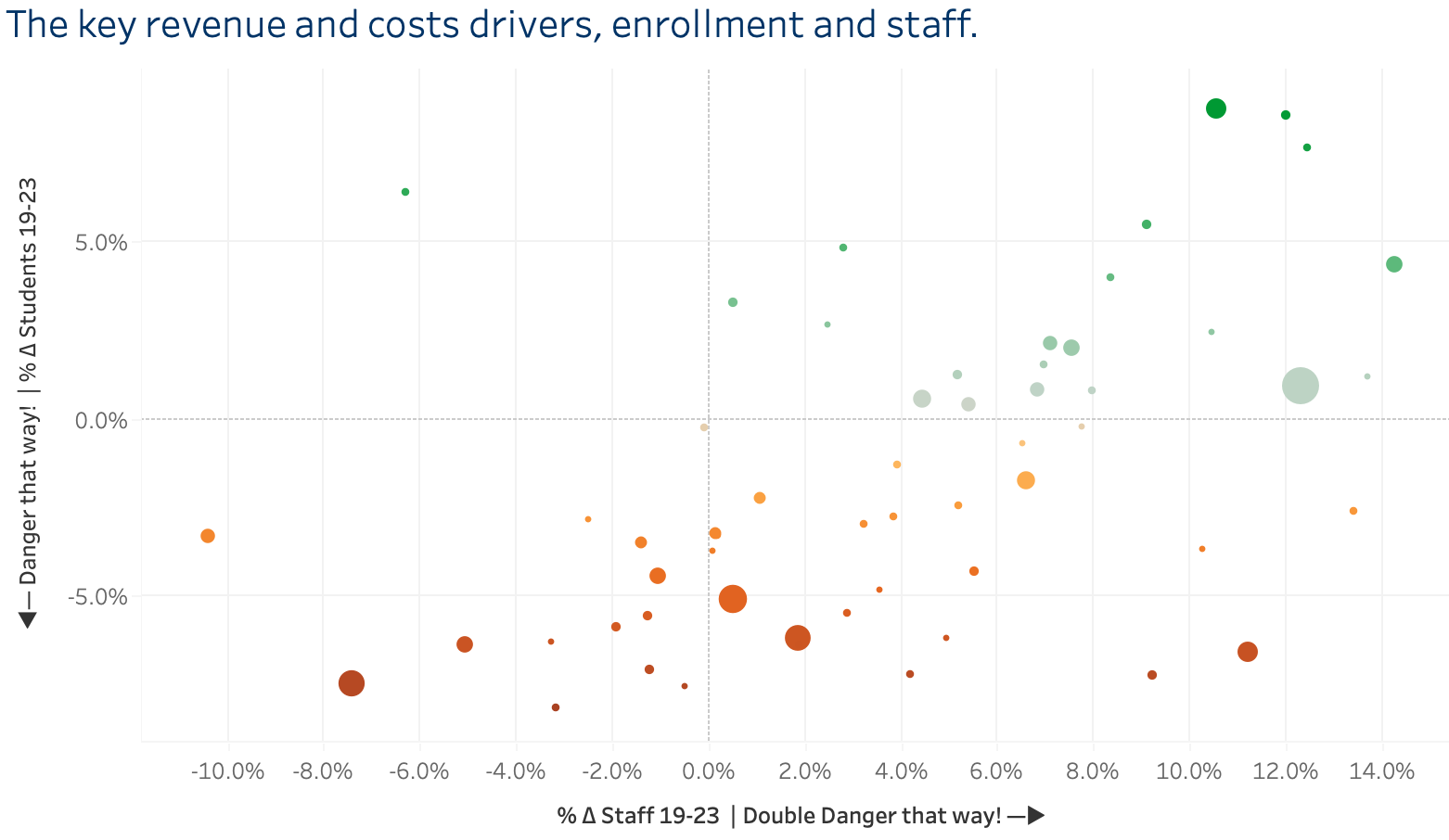

How this plays out district by district varies and we are working with clients to assess which districts are positioned to manage the change. It’s those that have controlled their largest cost driver, labor, and revenue source, enrollment. Each district (the bubbles below) has its own story.

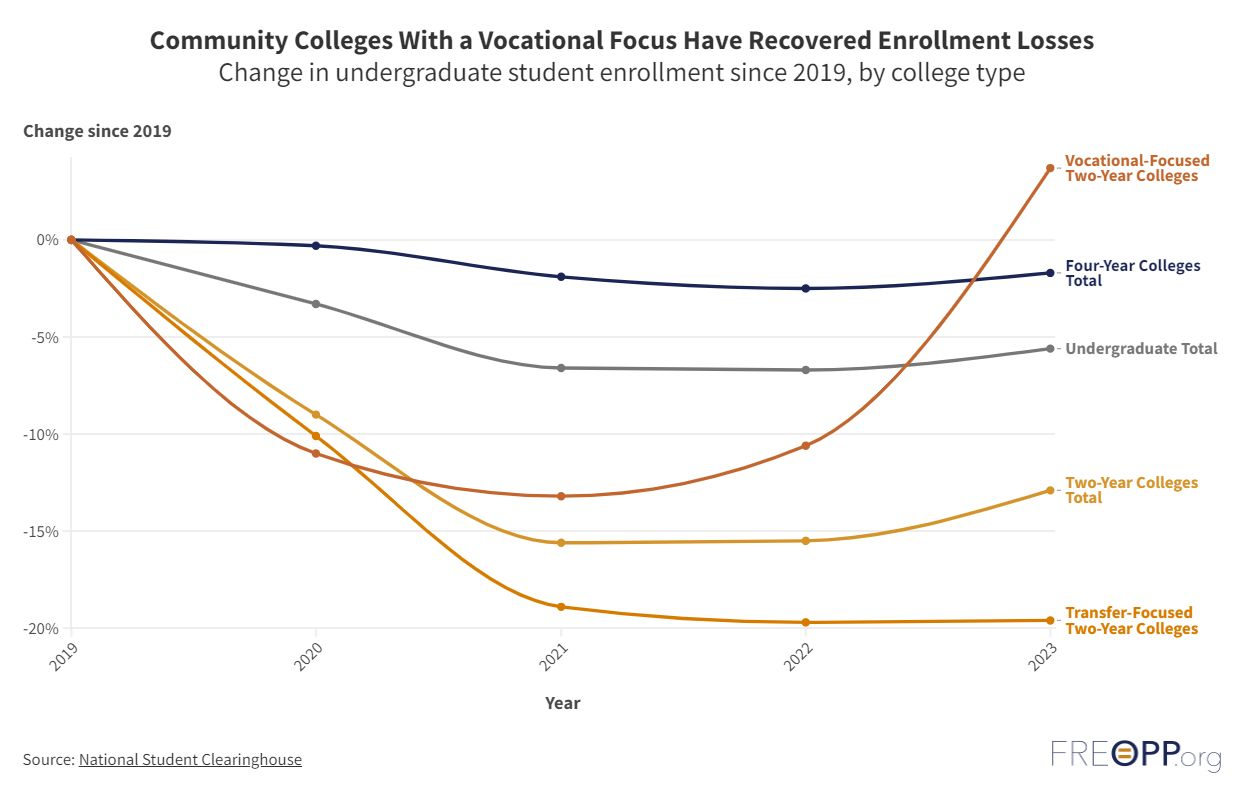

Beyond beltway politics, institutions of higher education also face a demographic cliff, amid a crisis of confidence and growing concerns about the value of a degree in a rapidly changing labor market.

Against that backdrop, it’s not easy to compartmentalize and even we have a hard time reporting “just the facts.” But that’s our goal. In the weeks to come, there will be lots more to cover and—as the facts evolve—we’ll report out.

Got questions for our research team? Let us know.

This article is sourced from Whiteboard Notes, our weekly newsletter of the latest education policy and industry news read by thousands of education leaders, investors, grantmakers, and entrepreneurs. Subscribe here.