Education investors are all asking us the same question.

What happens to edtech growth when pandemic-era stimulus funds dry up?

Short answer: the impact will be significant. And school districts nationwide are already facing the compounding effects of not just evaporating federal funds, but declining enrollment.

ESSER provided a generational level of new funding: the equivalent of ten years in Title I funding with the requirement that it be “spent” in just five.

But the fiscal cliff will impact every district differently.

Imagine a dual income household where one spouse earns $125,000 per year, and the other spouse earns $45,000.

If the second spouse loses their job, their aggregate income drops by more than 25%. But the short-term impact of that job loss on the couple would depend on a host of other factors.

Did they live on the $125K and save the $45K for retirement? Or did they need the $45K to cover their mortgage, car payments and basic living expenses? What if the job loss was offset by a decrease in childcare expenses—or spouse #1 received a 20% raise?

David DeSchryver and Hillary Knudson put together two charts that help to explain some of the factors that impact variability among post-ESSER budgets.

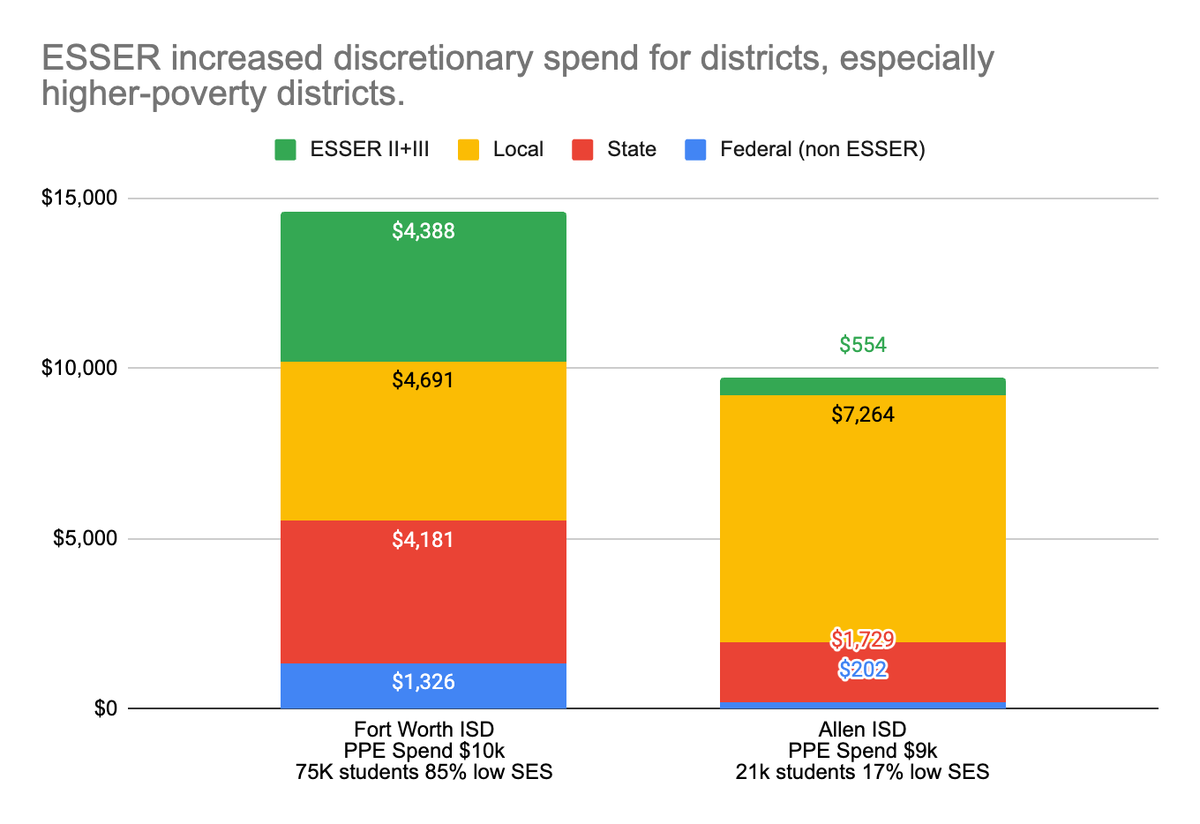

Poverty Level: The distribution of ESSER funds mirrored the Title I funding formula, which means high-poverty districts received more stimulus funding and are, in many cases, harder hit by the wind-down. The chart below illustrates the impact ESSER had on discretionary funding for two very different Texas districts.

|

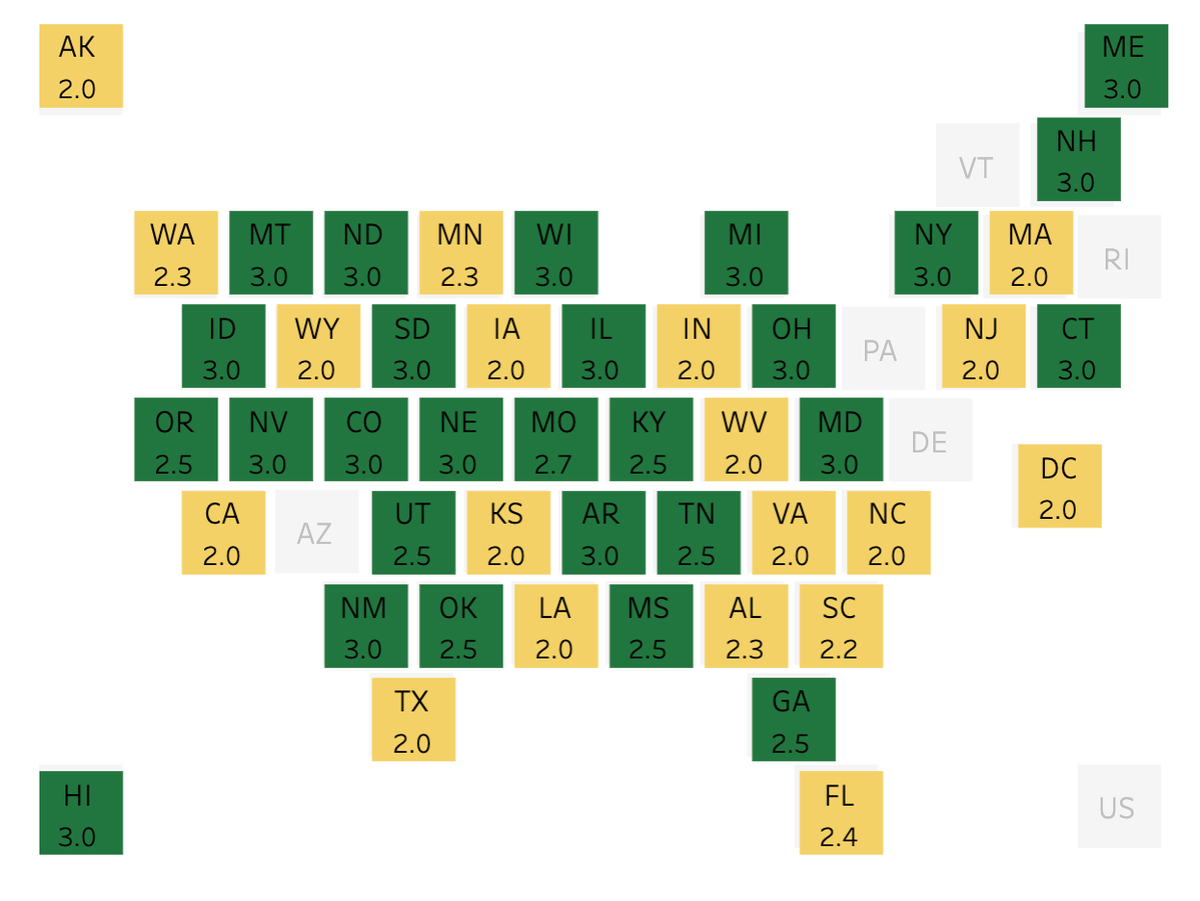

State and Local Budgets: State and local budgets vary. In some cases, education funding formulas are changing. It’s also quite common for local governments to raise taxes in order to maintain education spending.

Not a single U.S. state has decreased K-12 spending for the next fiscal year, but that doesn’t mean education budgets have kept pace with inflation or that districts will, in effect, “feel” an increase.

The following map shows whether a state’s education budget is down (red), level (yellow), or up (green). Gray boxes are states that do not yet have finalized budgets.

|

Leadership: Not all districts spent money on the same sorts of things.

And some are using the pullback to make hard—but perhaps overdue decisions—like cutting central office costs to preserve COVID-era tutoring investments. Districts that used short-term funds to make long term purchases (like new hires) are now faced with tough decisions.

Under the leadership of State Superintendent Christina Grant, Washington, D.C. used stimulus funds to invest in high-quality instructional materials and improvement to state standards that could have an enduring impact post-COVID.

She also incorporated evidence-based research into stimulus investments with an eye toward not just understanding what worked—but making the case for sustained investment when federal funds went away. The District just turned the corner on serving more than 10,000 students through a high-dosage tutoring program that appears to have a correlation with improved attendance and is expected to move the needle when assessment results are published in August.

The District is now stepping up with a $4.8M local set-aside to sustain the program.

June 14 was Dr. Grant’s last day in office. She’s now off to lead the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard where her leadership—and experience—will no doubt impact the lives of students and educators nationwide!

This article is sourced from the opening letter of Whiteboard Notes, our weekly newsletter of the latest education policy and industry news read by thousands of education leaders, investors, grantmakers, and entrepreneurs. Subscribe here.